When an Innocent Person is Framed

We’ve all seen movies and television programs in which a totally innocent person is “set up” by the police or their agents and accused of a crime. Drama ensues as the unjustly accused protagonist struggles to prove his or her innocence. Often, the narrative takes liberties with legal principles and practices, and the story can be quite unrealistic. But details aside, is it possible for an innocent person to be intentionally set up for an arrest and prosecution? We’re not talking about accidentally arresting the wrong person, such as in a case of mistaken identity. Rather, we are talking about a purposeful “frame.”

We’ve all seen movies and television programs in which a totally innocent person is “set up” by the police or their agents and accused of a crime. Drama ensues as the unjustly accused protagonist struggles to prove his or her innocence. Often, the narrative takes liberties with legal principles and practices, and the story can be quite unrealistic. But details aside, is it possible for an innocent person to be intentionally set up for an arrest and prosecution? We’re not talking about accidentally arresting the wrong person, such as in a case of mistaken identity. Rather, we are talking about a purposeful “frame.”

Many of my clients are involved in the health, fitness and sports fields, including competitive bodybuilding. I was recently contacted by a competitive female bodybuilder in a southwestern state accused of selling steroids inside the gym she owned with her husband. We’ll call her “Jane” (not her real name). Jane had never been in any type of legal trouble before, and was understandably quite upset because she swore she absolutely did not do it. I took the case, and after speaking with her at length, I was 100% convinced that she was falsely accused.

The case against Jane was based on the word of an informant. Informants, also known as “rats” or “snitches,” have been a key asset of law enforcement in the 40-year-old War on Drugs. Informants are usually people who get busted and, in return for leniency from the prosecutor or judge, “cooperate” with law enforcement to help bust others, such as by making “controlled buys” wearing hidden recording devices. These transactions must be closely monitored to ensure the integrity of the evidence. The axiom among drug police is, “Never trust an informant.” If agents do a shoddy job of supervising, the snitch can fool them. After all, deceitfulness is what makes a successful informant! An informant can steal a portion of the buy money or drugs. Lazy cops can even make it possible for a rogue snitch to frame a totally innocent person.

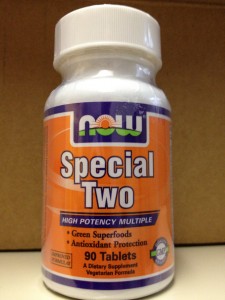

Narrowing down the relevant facts as much as possible, here’s what the case consisted of: the informant, facing his own felony drug charges, targeted Jane to the local drug task force by claiming he’d arranged by phone with her to go to her gym, give her money, and receive a bottle of multivitamins with a hidden vial of testosterone inside. Later that day, the informant met with the cops. They patted him down for money or drugs and did a quick search of his car. Finding nothing, they gave him the cash, put a wire on him, and let him drive to the gym while they waited nearby. After a lengthy recorded conversation between the informant and Jane about every conceivable aspect of bodybuilding and nutrition, he asked for the bottle of multivitamins. She rang up the sale in the cash register and gave him the bottle. Shortly afterward, he delivered the bottle to the cops and inside was the vial of testosterone. The police viewed it as an open and shut case, as did the prosecutor. He offered my client a “no jail” plea (straight probation, but a felony conviction); however, if she refused it and went to trial and lost, she would face over ten years in prison.

I had a client I believed was 100% innocent. Two “discovery” procedures requiring the prosecutor to disclose certain information upon demand in advance of trial enabled me to prove it. First, I obtained a copy of the audiotape of the transaction. When I listened to it, I understood what the informant had done. Second, I demanded to interview the informant before trial. The opportunity to interview or “depose” a prosecution witness other than in a pre-trial court hearing or during the trial itself is not afforded in most jurisdictions. Luckily for Jane, this was one of the few jurisdictions permitting this. So, I packed my bag and flew to the Southwest to nail this lying rat to the wall.

The critical moment in the transaction occurred after the snitch received the bottle but before he delivered it to the police. He asked Jane if he could use the bathroom. Then he went in and closed the door. Hmm, why couldn’t he wait five minutes until after he delivered the evidence? The reason, he claimed under my cross-examination of him, was a desperate need to urinate. I pressed him further and he took the bait. He droned on about the uncomfortable urgency of his problem, and then detailed his glorious relief at emptying his bladder. But he’d walked into my trap. The wire he had been wearing was still recording in the bathroom. Everything that happened in there was preserved on audio. When I played the recording for everyone in the room, the prosecutor’s face turned ashen. There wasn’t a “tinkle” to be heard. Instead, there was the unmistakable sound of vitamin-sized objects hitting porcelain as the informant dumped them into the bowl and flushed, making space in the vitamin bottle for him to insert the vial himself and frame Jane. Client exonerated … and case rightfully dismissed!

Why did the informant frame Jane? Presumably he wanted his sweetheart deal, didn’t want to set up any real drug dealers, and figured a heavily muscled female bodybuilder might be a believable mark for a steroid allegation. Where he hid the vial isn’t certain, but casual pat-down searches and quickie car checks are insufficient to catch a devious informant. And agents should never have taken the informant’s word about the original phone call – if it had been recorded, none of this injustice would have happened.

Hopefully, informant frame-ups of innocent clients are rare, and can be prevented by attentive police. But it’s important to recognize that these sorts of nightmares can and do take place, and that ultimately it’s the job of the criminal defense attorney to employ smart strategies and to fight hard to set things right.